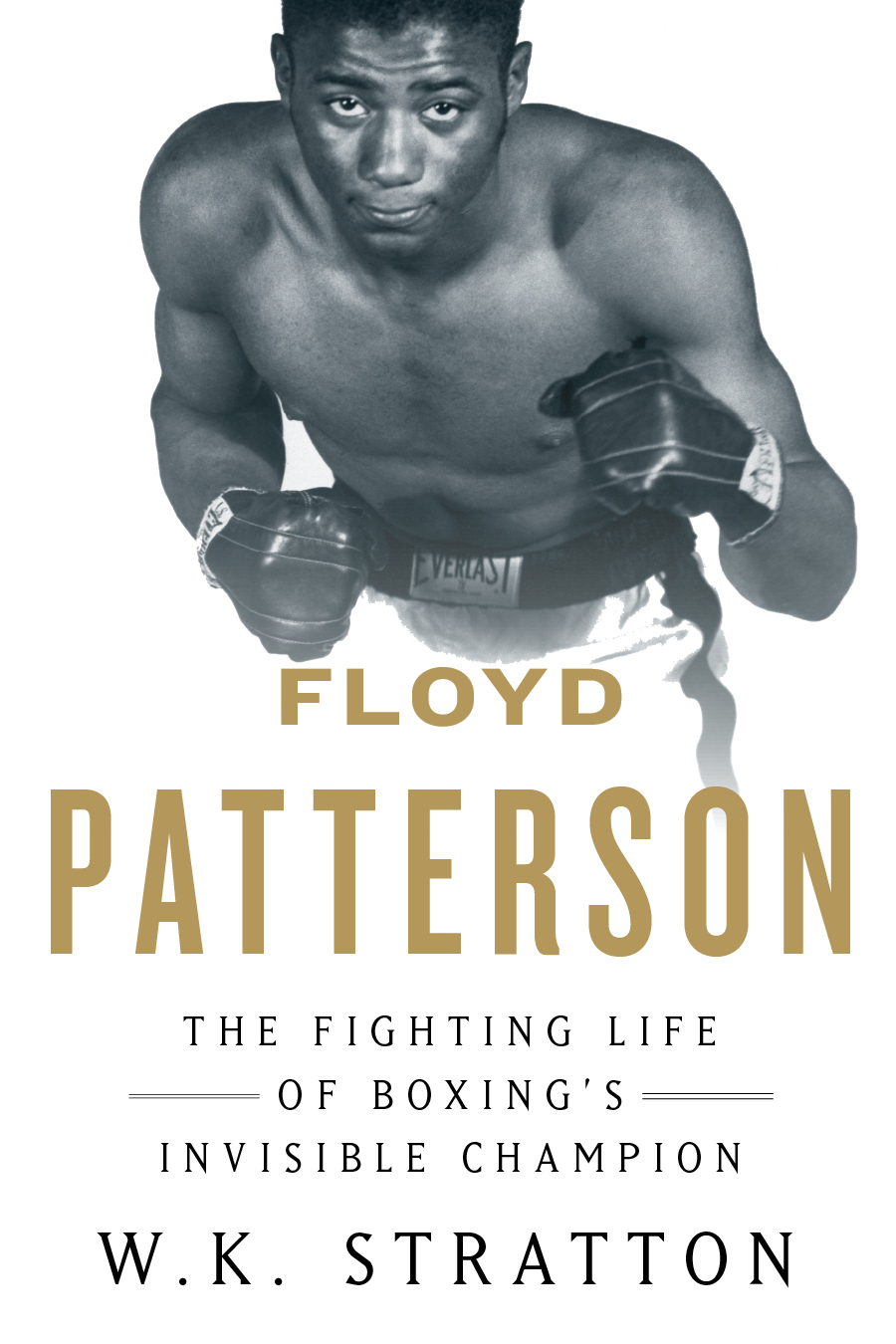

Floyd Patterson

The Fighting Life of Boxing's Invisible Champion

A Q&A With Author W.K. Stratton

Why Floyd Patterson?

Patterson was an important figure in

American sports. He was among the greatest amateur boxers the U.S. has

ever produced. His achievements along with the other members of the 1952

U.S. Olympic Boxing Team have been largely forgotten. Some of Patterson’s

pro accomplishments likewise have been forgotten: the youngest heavyweight

champ, the first to win the heavyweight title twice, etc. Also, his

contributions to the civil rights movement have been overlooked. Plus

there were other elements of his story that are compelling: his overcoming

childhood trauma, his relationship with his manager Cus D’Amato, his

relationships with rivals like Muhammad Ali and Sonny Liston, and so forth.

Much about Patterson had been lost in the glare of Muhammad Ali’s career.

I felt as if it was time to bring Floyd back into the light.

What Is Your Interest in Floyd Patterson?

I was a kid and young man during the

last golden era of professional boxing, the era that began roughly around 1960

and ended more or less in 1987 with the Hagler-Leonard fight. I was a fan.

As a result, I saw some of the greatest fighters the sport has ever known.

Patterson was an important figure during that era, and of all those great

fighters, he arguably had the most interesting back story. On the surface,

he seemed to be the least likely of prizefighters. As Gay Talese told me,

there were any number of endeavors Floyd could have entered and been successful,

so why boxing? The answer is, in Floyd’s case, it couldn’t be anything

else because boxing had a meaning to him that nothing else in life could match.

My own experience in the boxing gym has exposed to me men and women who have

that same sort of feeling. So Patterson’s story fascinated me for years,

and the more I learned about him, the more fascinated I became. Finally I

took the plunge and wrote the book. I did an extraordinary amount of

research on the book. Relatively few of the men Floyd fought were still

alive or were capable of being interviewed at the time of my research, but I did

receive valuable insight from an afternoon I spent with one of them, Roy “Cut ‘n

Shoot” Harris. A day I spent with Gay Talese, who likely penned more

insightful words about Patterson than any other journalist, was extremely

revealing. A 1950s boxer (who never fought Patterson but knew him

socially) turned actor named Jim Brewer shared stories about Floyd from social

occasions in Hollywood that revealed a great deal about Patterson’s personality.

I was never able to interview Norman Mailer (although a couple of people close

to him did their best to arrange it during his waning days), but I was able to

get access to his letters and other personal items in the Harry Ransom Center at

the University of Texas. I spent a couple of days poring over handwritten

notes and other fascinating tidbits – even phone numbers scrawled on matchbook

covers – that pertained to Patterson fights. Mailer was quite the hoarder

when it came to items related to his career, and that’s good. I found bits

and pieces here and there that provided good background material, even though I

didn’t quote them directly in the book, such as letters in the collection of the

New York Public Library to Floyd from the one-time director of the Wiltwyck

School. That sort of thing. But the biggest part of the research was

working my way through thousands of newspaper and magazine articles written

about Floyd and his rivals, many of which wound up in the wonderful collection

of the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas. I

also read dozens of books for this project.

Why Do You consider Patterson To Be “The Invisible

Champion”?

Of course, the primary reference is to

Ralph Ellison’s classic novel, Invisible Man.

You may recall that the unnamed narrator of that great novel lives in a “hole”

in a basement, cut off from people. Patterson found peace as a child in a

kind of hole near a subway station, this one used to store tools by the train

crews. Like the narrator of the novel, young Floyd found some peace in his

hole. That novel appeared about the time Floyd was winning his Olympic

gold medal, and, among its other attributes,

Invisible Man seems to speak for a generation of

young black men who find themselves socially invisible. Growing up in

Brooklyn, Floyd could identify with this sense of invisibility. Even when

he became champion – one of the most famous people in America – he found himself

treated as if he was invisible when he tried to get a meal at Kansas City

restaurants. So: the connection to the novel. But there’s more.

As a champ, Floyd liked to stay out of the public eye as much as he could.

He trained incessantly at remote training camps, even when he didn’t have a

fight scheduled. He always felt uncomfortable when people looked at him,

so he liked to stay “invisible” as much as he could. Also, against the

glare of Ali’s light, Floyd’s accomplishments as champion have become

invisible, especially to younger readers. So there are a number of ways in

which Floyd is the invisible champ.

How Would Floyd Want To Be Remembered?

Foremost, as a good American. He

told former boxer and actor Jim Brewer that his proudest achievement was winning

a gold medal at the 1952 Olympics. That meant more to him than becoming

heavyweight champion of the world because the latter was an individual

accomplishment: He felt like he won the gold medal for all of America.

I think Floyd would also be proud of his contributions to the civil rights

movement in the 1950s and ‘60s, and I think he would be proud that he didn’t

give in to more radical elements in the latter 60s and early 70s, even though it

was fashionable to do so. I also think Floyd would like to be remembered

as a good Catholic. And, very important, as a “boxing man,” as he described

himself, someone who received all the opportunities in life that he did because

of boxing and someone who gave back all he could to the sport.

How Important Was Floyd To The Civil Rights

Movement?

Floyd was very important, although he

aligned himself with the more moderate factions of the movement than with the

more militant. He gave financial support to Catholic clergy attempting to

desegregate Arkansas at a time when no black athletes of his stature were taking

that sort of political stand. He refused to fight in a segregate arena in

Miami at a time when Miami was much more of a Southern city than the

cosmopolitan city it has since become. No other black athlete could or

would do that at the time. He supported Martin Luther King and traveled to

Birmingham, Alabama, at the peak of the civil unrest there to show support for

King’s civil rights activities. He was selected for lifetime membership in

the NAACP for his work and became a leading fundraiser for that organization.

On a more personal level, he was active in supporting both the Wiltwyck School

and Floyd Patterson House, two organizations that functioned to help troubled

New York City boys – the majority of whom were black – overcome crime and

violence while receiving an education.

W.K. Stratton. All rights reserved.